How does sound taste?

“One cue to Systems Intelligence (SI) is to become more sensitive on the channels of input. The senses form an interface with the outer world and if a person wishes to succeed in the context of complex systems and involving interaction and feedback, she needs to be acute on what her senses tell of the world.”

We tend to think of taste as a closed-loop system between the mouth and the nose, but the physiological reality is far more wired. There's a new frontier of sensory design emerging, and we are seeing the collapse of the wall between what we hear and what we consume.

From bone-conduction candy that plays hip-hop through your teeth to Michelin-starred dishes that demand you wear headphones, here's the science and the strange new reality of how sound changes taste.

The term "sonic seasoning" refers to the deliberate use of sound to alter the perception of taste. The most famous finding in this field is the "pitch-taste" connection.

The "Sonic Seasoning" Effect

Back in 2012, researchers at the Crossmodal Research Laboratory at Oxford University found something remarkable: a consistent, universal mapping between sound frequency and taste. High-pitched sounds make food taste sweeter (think wind chimes, piano keys, or tinkling bells). Low-pitched sounds emphasize bitterness (brass instruments, heavy bass, the rumble of a cello). [7]

In one study involving bittersweet toffee, participants rated the exact same piece of candy as 10% sweeter when listening to a high-pitched soundtrack and 10% more bitter when listening to a low-pitched one. Same toffee. Same mouth. Different sound.

Try it yourself: if you're drinking dark coffee or eating dark chocolate, listen to high-frequency "tingling" sounds. Tell me if you notice the bitterness recede, revealing hidden sweet notes without adding of sugar.

Six Real-World Examples of "Edible Audio"

1. AI Can Now "Compose" Flavors

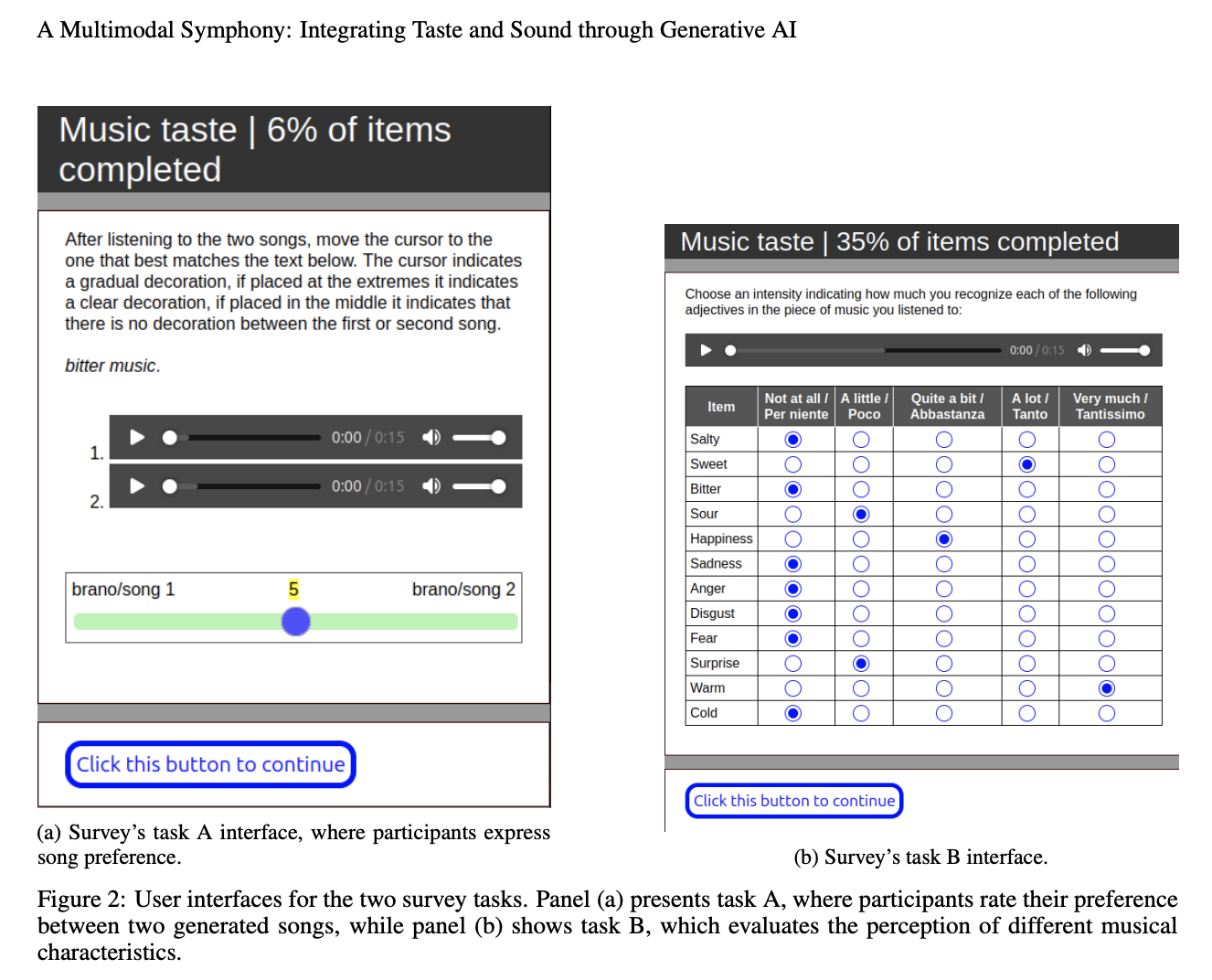

In 2025, researchers published one of the first studies proving that machines can understand the taste-sound connection well enough to generate it themselves [1]. They fine-tuned Meta's MusicGen AI and fed it data on taste-sound correspondences: bitter equals low pitch and dissonance, sweet equals consonance and high pitch. Then they asked it to generate new music based only on taste prompts like "very sour."

Here's what happened: 111 human listeners consistently matched the AI-generated music to the correct taste (sweet, sour, bitter) without being told what the AI was targeting. This proves that the link between sound and taste isn't just a vague human feeling. It's a data-driven pattern distinct enough for an artificial intelligence to replicate.

We're entering a world where a machine can "compose" a flavor profile through sound alone.

2. The Lollipop Star: Flavor via Bone Conduction

The wall between hardware and food is falling. The Lollipop Star (and similar products like Amos TastySounds) is a prime example of this convergence.

It uses bone conduction technology. The candy itself acts as the transmitter. When you bite down, vibrations travel through your teeth and jawbone directly to your inner ear. You "hear" the music inside your head, but the person standing next to you hears nothing. It turns the act of eating sugar into a private concert, merging the sensory inputs of sweetness and sound into a single neural event.

3. The "Auditory Seasoning" App

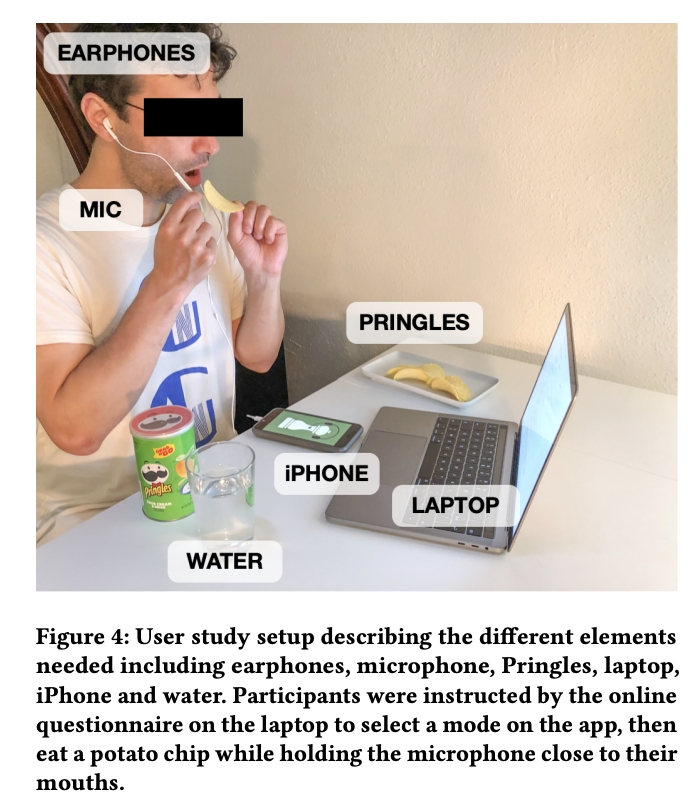

In 2023, researchers from MIT Media Lab, Northeastern, and the University of Copenhagen developed a mobile app that uses a bone-conduction headset to capture the sound of you chewing and then alters it in real-time before playing it back to you [3].

Participants ate Pringles while the app manipulated the audio feedback of their own chewing. Simply amplifying the volume of the chew made the chips taste significantly stronger in flavor, not just crunchier. When the chewing sound was deepened with a low-pass filter, participants ate slower and felt fuller faster, suggesting that "heavy" sounds might help regulate appetite.

4. Emotion Overpowers Pitch

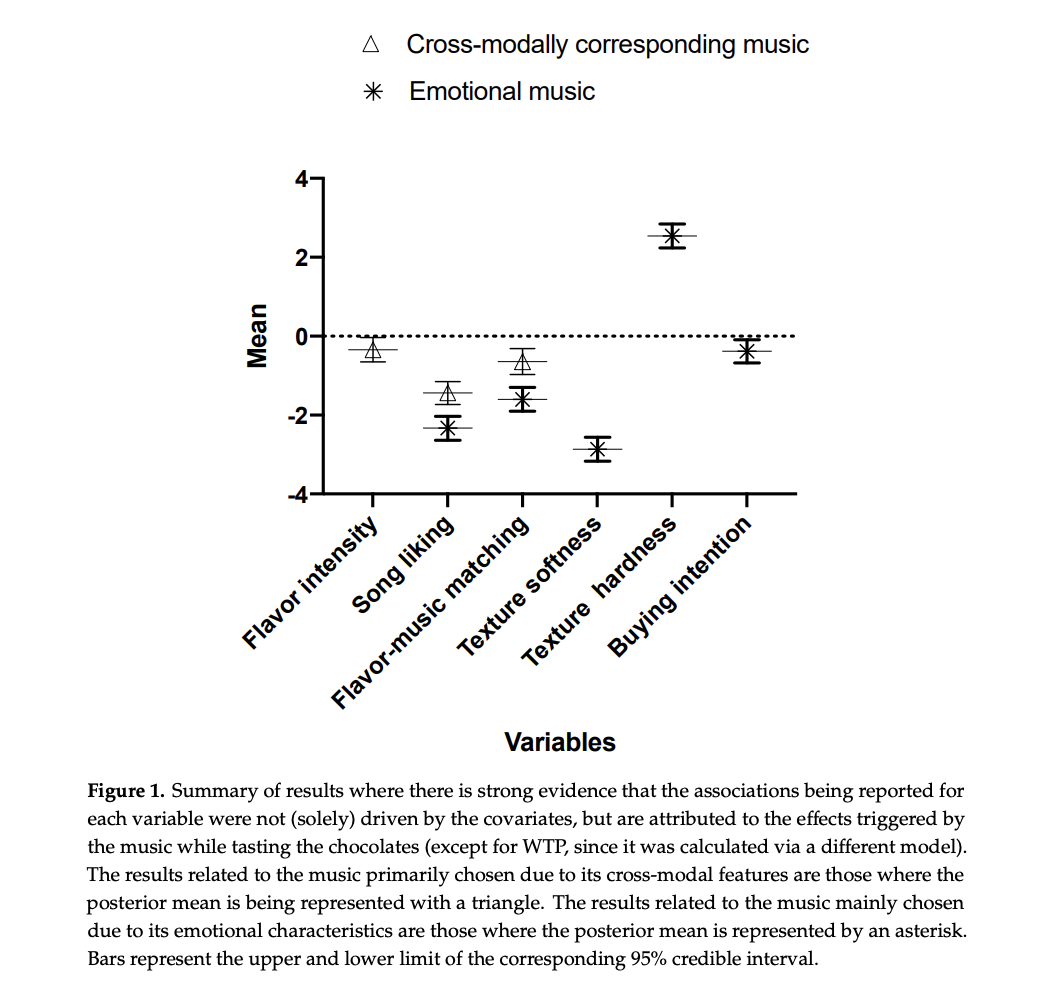

For years, we thought "high pitch" was the master key to sweetness. But a 2020 study with 1,611 participants added a new variable: emotion [4].

They found that "positive" music (music that makes you feel happy) increased the perceived sweetness of chocolate even more effectively than just "high-pitched" music. It also made the chocolate feel creamier and softer in the mouth. Conversely, "negative" or dissonant music didn't just make the chocolate taste bitter; it made the texture feel harder and the flavor less intense.

This suggests that what we're really responding to isn't just frequency. It's emotional resonance. And that resonance has the power to change not just taste, but physical texture.

5. The "Sound of the Sea": Modern Gastronomy

This is perhaps the most famous dish in modern multisensory gastronomy, created by chef Heston Blumenthal at The Fat Duck [5]. The dish is sashimi and "sand" made from tapioca, served on a glass box containing real sand. Diners are given an iPod inside a seashell to listen to crashing waves and seagulls while they eat. "By playing something that is congruent with what you're eating, it enhances the emotion of that dish," Blumenthal explains.

Research confirmed that the ocean soundtrack made the seafood taste significantly saltier and fresher than when eaten in silence or with generic restaurant noise. The sound "primed" the brain to detect specific savory flavors.

6. Why Airline Food Tastes Bad (It's the Noise)

Why do some people like drinking tomato juice only on airplanes? There's a scientific reason [7].

Background noise at 85 decibels (the roar of a jet engine) suppresses our ability to taste sweetness and saltiness. But here's the twist: loud white noise does not suppress umami, the savory taste found in tomatoes, mushrooms, and soy sauce. In fact, it might even enhance it.

In the noisy environment of a cabin, a bland meal becomes even blander, but a savory, umami-rich tomato juice suddenly tastes like the most flavorful thing on the menu.

Why This Matters: The Synesthetic Future

We used to design for senses in silos: a chef worried about taste, a musician about sound, a designer about visuals. These findings reveal that perception is synesthetic by design. Our brain constantly integrates these inputs.

This isn't just about taste and sound. It's about realizing that all of our senses are in constant conversation, and we've been designing for them as if they're strangers.

Once you accept that sound changes taste, you start asking: what else is connected? How does scent change what you see? How does texture change what you hear? How does time change how you experience space?

And suddenly, you're designing a meal & a system, a song & an environment, a product & a perception.

That's the future I'm interested in. Not because it's profitable (though it will be). Not because it's novel (though it is). But because it's true.

Our senses were never separate. We just didn't have enough tools to design for their integration. Now we do.

And the question is: are we going to use that knowledge to create experiences that make people feel more alive, more present, more connected to what they're consuming?

That's why this matters.

Selected References for Further Reading:

Spanio, M., Zampini, M., Roda, A., & Pierucci, F. (2025). A Multimodal Symphony: Integrating Taste and Sound through Generative AI. Frontiers in Computer Science. (Link)

Lollipop Star company

Kleinberger, R., Van Troyer, A., & Wang, Q. J. (2023). Auditory Seasoning Filters: Altering Food Perception via Augmented Sonic Feedback of Chewing Sounds. Proceedings of the 2023 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. (Link)

Reinoso-Carvalho, F., et al. (2020). Blending Emotions and Cross-Modality in Sonic Seasoning: Towards Greater Applicability in the Design of Multisensory Food Experiences. Foods (MDPI). (Link)

Mark Sansom (2020). The Fat Duck at 25 – how Heston Blumenthal defined modern gastronomy. The World’s 50 Best Stories. (Link)

Yan, K. S., & Dando, R. (2015). A cross-modal role for audition in taste perception. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance (Link).

Knöferle, K., & Spence, C. (2012). Crossmodal correspondences between sounds and tastes. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. (Link)

Spence, C., et al. (2021). Commercializing Sonic Seasoning in Multisensory Offline Experiential Events and Online Tasting Experiences. Frontiers in Psychology. (Link)

Thank you for thinking with me. This piece is part of Ode by Muno, where I explore the invisible systems shaping how we sense, think, and create.

The quote at the intro is from the book, Systems Intelligence.