Third places are disappearing — here’s the data

“The systems perspective wants to see the world as composed of systems, to examine these entities as wholes and assumes the wholes to be primary to their parts.”

Overview

My last post was a reflection on my own experience with disappearing third places. This post is the data version, a look at what’s actually happening at the national level.

What this analysis uses

For this analysis and all the visualizations, I used the National Neighborhood Data Archive (NaNDA), which tracks establishment counts across U.S. Census Tracts from 1990–2021 across six sectors: grocery, restaurants, retail, recreation/fitness, arts/entertainment, and hospitality. It provides a three-decade view of where Americans could eat, shop, exercise, and gather.

What the data measures

Total establishment counts

Per-capita density (venues per 1,000 people)

What the data captures well

Long-term infrastructure trends

Geographic access patterns

Category-level growth or decline

What the data does NOT capture

How people actually use these places

Time spent in venues

Digital or hybrid substitutes

Informal gathering spaces (parks, churches, homes)

Citation

re3data.org: National Neighborhood Data Archive (NaNDA)

https://doi.org/10.17616/R31NJNQA

Key Terms

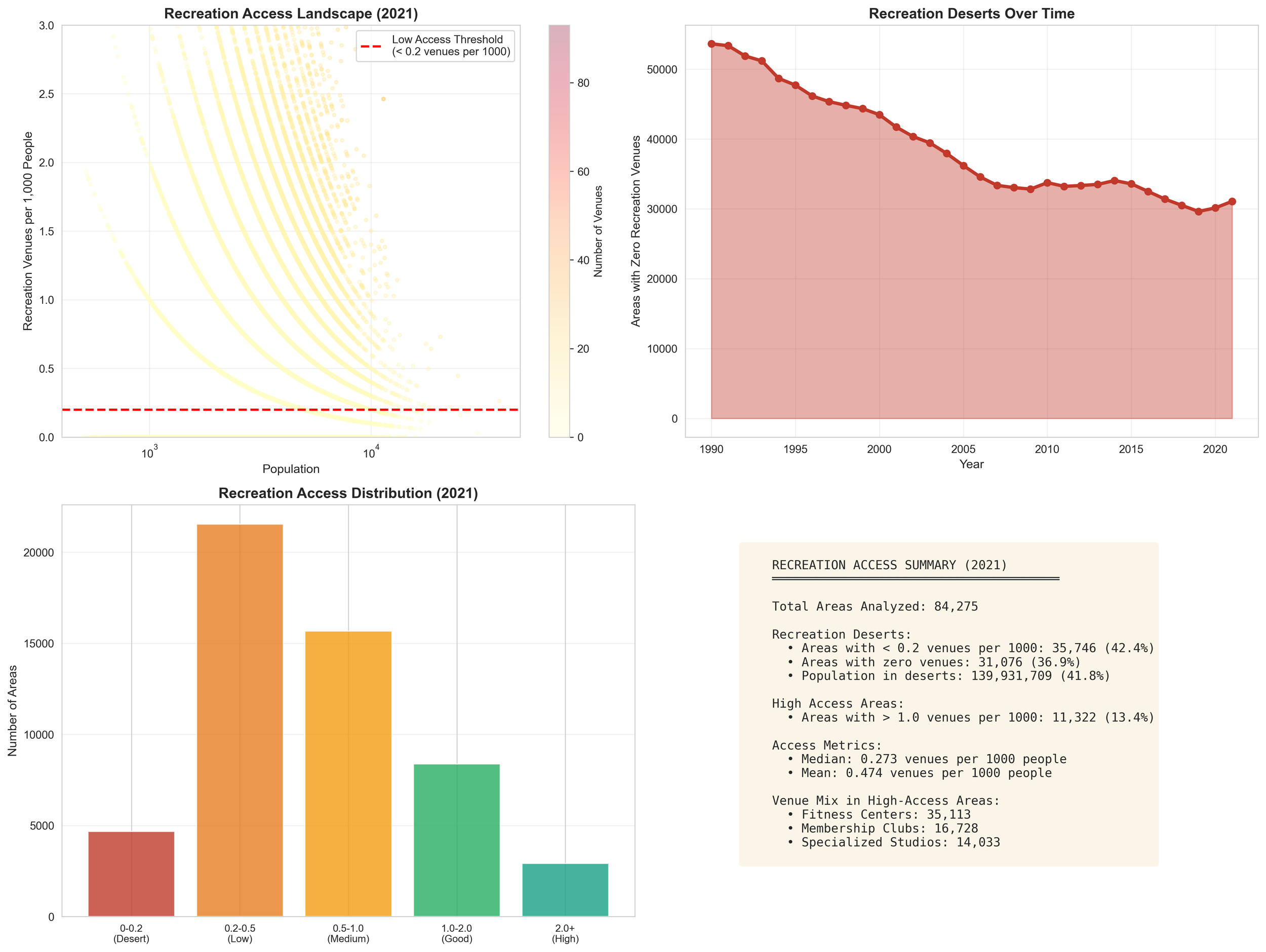

Recreation desert:

Neighborhood with <0.2 recreation venues per 1,000 people.

Example: a tract of 5,000 residents with only 0–1 gyms, pools, or studios.

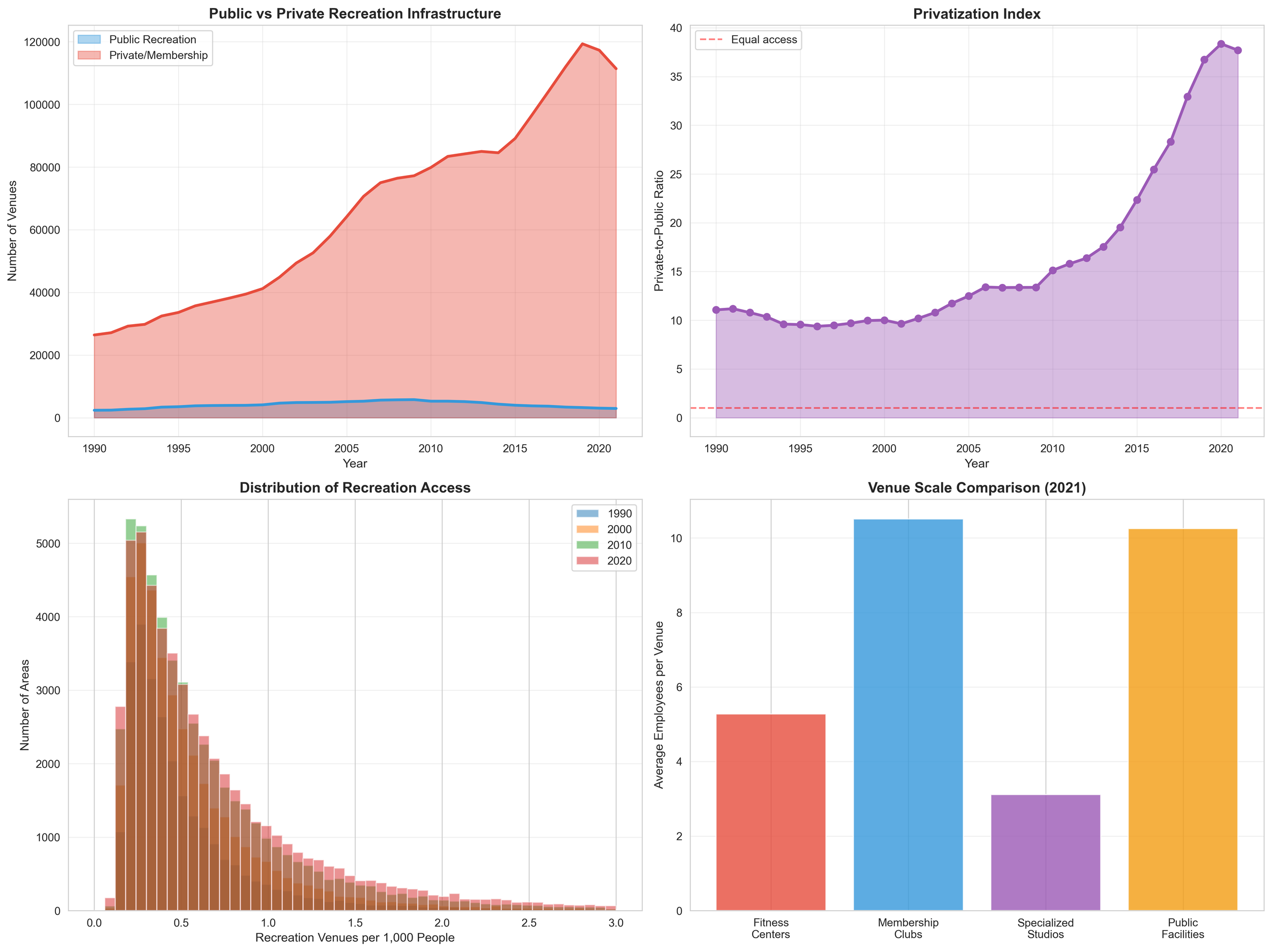

Privatization index:

Ratio of private fitness venues to public facilities.

Example: 10:1 = ten private gyms for every one municipal option. Higher = more paywalled access.

Per-capita density:

Establishments per 1,000 people.

Prevents false growth signals when population increases.

Third place:

Spaces that are not home and not work (cafés, barbershops, bars, parks).

They matter because they support casual, low-stakes interaction.

Insight 1: the access gap

42% of Americans live in recreation deserts. 58% live in retail deserts. These are neighborhoods with almost no gyms, no studios, no stores, no casual places to go.

These areas are not “underserved.” They are unserved, meaning the market is kind of wide open.

The venues that disappeared (bowling alleys, department stores, community pools) left behind:

empty real estate

old habits

unmet demand

Someone will rebuild something in that space. The open question is whether the replacement will create community or extract money.

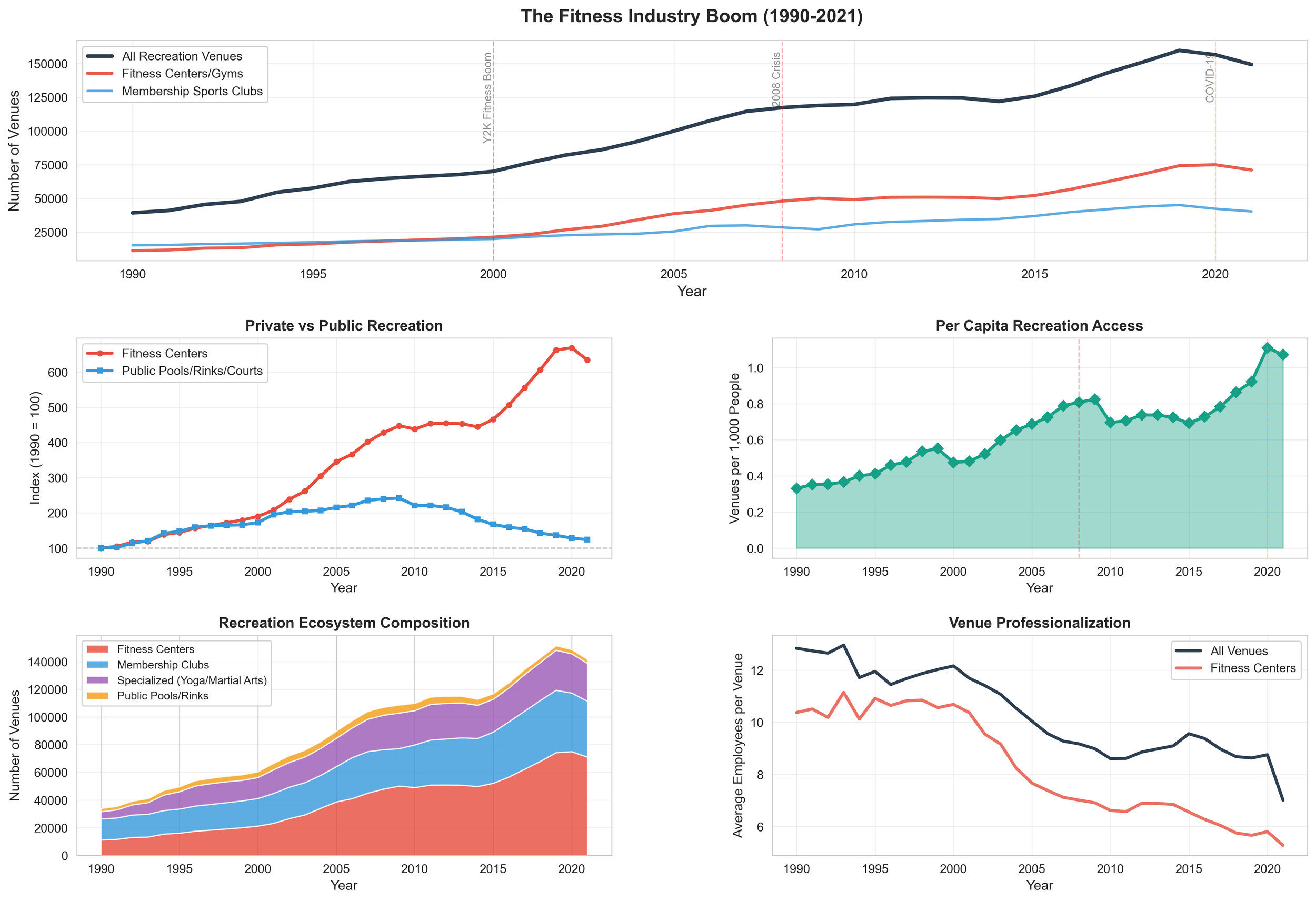

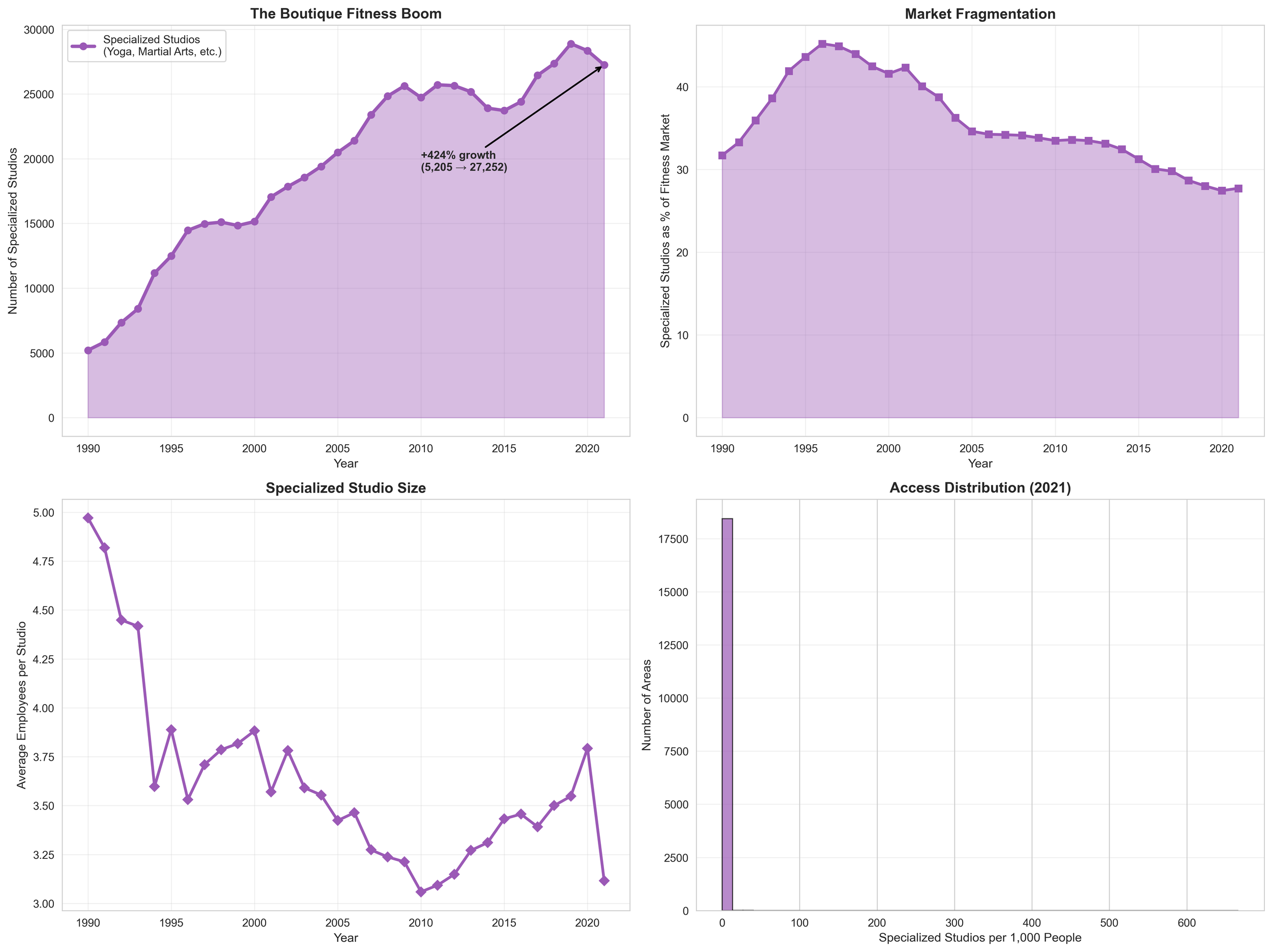

Insight 2: membership replaced location

The privatization index grew from 10:1 to 40:1, meaning there are now 40 private gyms or studios for every 1 public facility. As recreation became membership-based, how people choose where to gather changed.

How it works now id that identity chooses the brand & proximity chooses the branch.

People no longer pick the closest gym, café, or club. They pick the one that fits who they are, then choose the nearest location within that brand.

Examples:

ClassPass: choose the type of studio you identify with → then pick the closest option.

Equinox, Solidcore, Pure Barre, Orangetheory: join for identity → attend based on proximity.

SoulCycle / Barry’s / Rumble: brand first → nearest studio second.

Trader Joe’s: choose for culture → shop at the closest one.

Pickleball and tennis clubs: choose the sport/scene → play at the nearest club.

REI Co-op, Lululemon run clubs, climbing gyms, ceramics studios: same pattern.

The core shift is that identity narrows the option set, and convenience chooses from inside that set.

Gathering is now curated and membership-based, not primarily incidental or proximity-driven.

Insight 3: Third places became private spaces

As public third places declined, private businesses absorbed their role. Many now function as community hubs even if they weren’t designed for it.

Examples of private third places:

Pickleball clubs, tennis clubs, Pilates and reformer studios

Running and walking groups

Trader Joe’s (loyalty culture)

Cafés, hotel lobbies, bookstores with seating

Ceramics studios, climbing gyms, makerspaces

Dog parks, dog cafés, pet-based events

These are all social spaces inside private venues, not public infrastructure.

New third places that aren’t traditional venues:

Digital → physical groups (Discord meetups, Substack communities)

Retail-run communities (REI classes, Lululemon run clubs)

Parking-lot events (farmers markets, food trucks, church-lot events)

Micro-venues inside bigger venues (bookshop cafés, grocery-store seating)

Membership-based spaces (Soho House, WeWork, private social clubs)

The opportunity is not creating new venues. It’s improving the places where people already gather. Some examples:

Gyms with lounge areas and events outperform gyms that only sell workouts.

Cafés with seating and long stay-times become real hubs.

Pickleball and tennis centers become community drivers when they add mixers and programming.

Grocery stores create third places when they add cafés, demos, or classes.

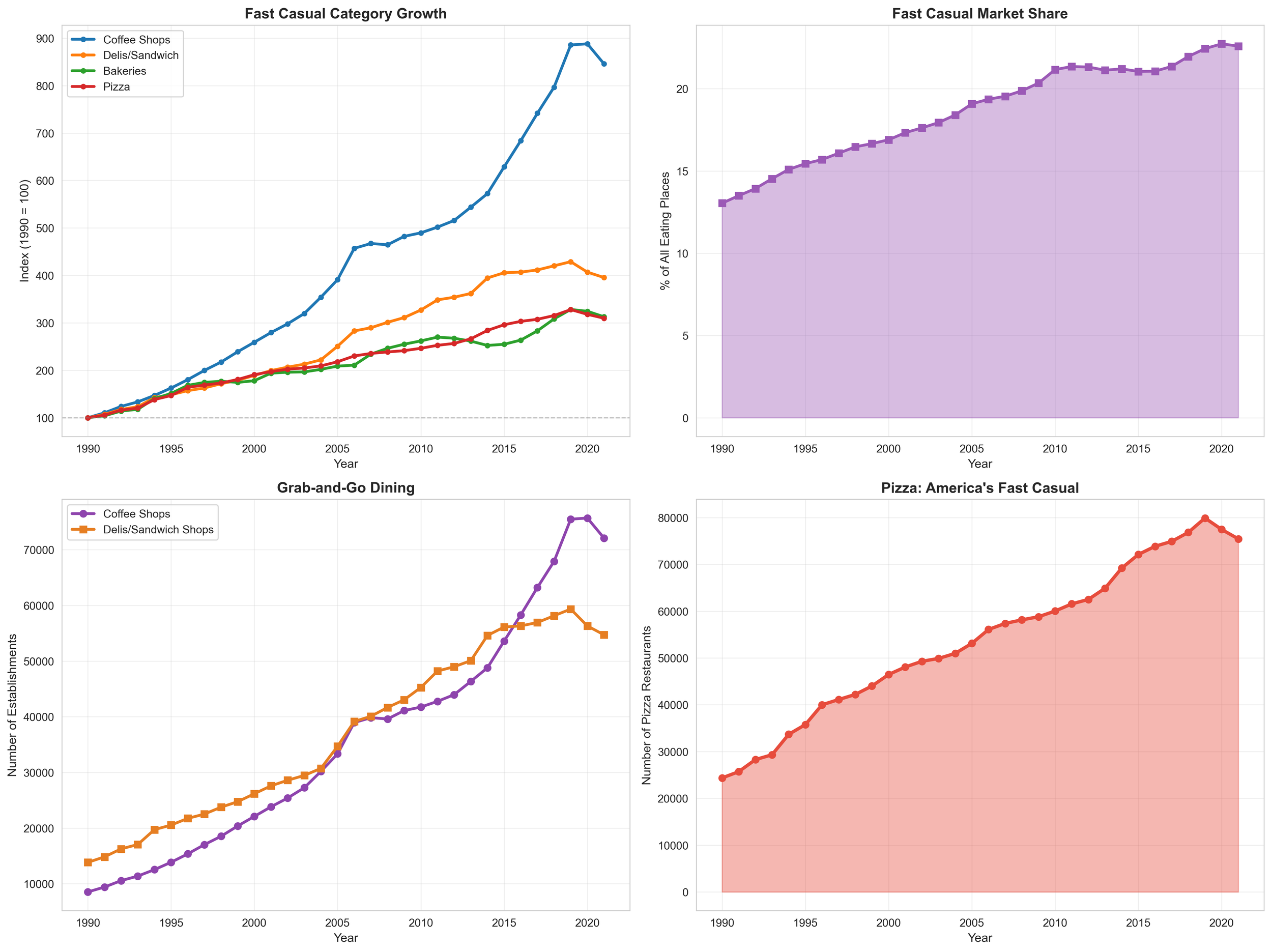

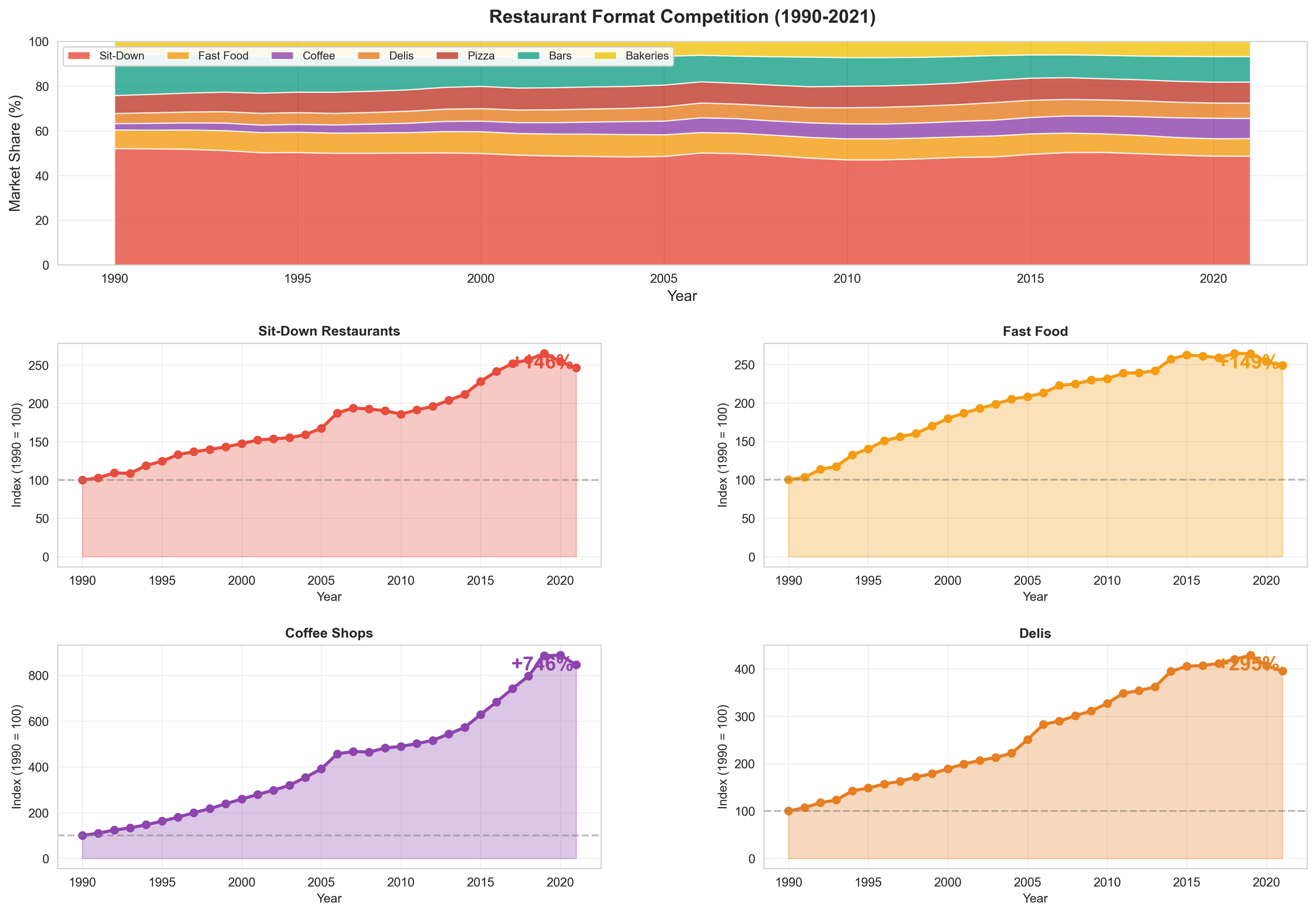

Insight 4: speed over lingering

The formats that grew fastest:

fast food

coffee shops

fast casual

The formats that grew slowest:

sit-down restaurants

Spaces designed for lingering are less profitable than quick transactions.

But the flip side is important: places designed for staying are now rare, which creates premium opportunity.

The sit-down restaurants that survive will win because they offer what most places no longer do: time, comfort, and a reason to stay.

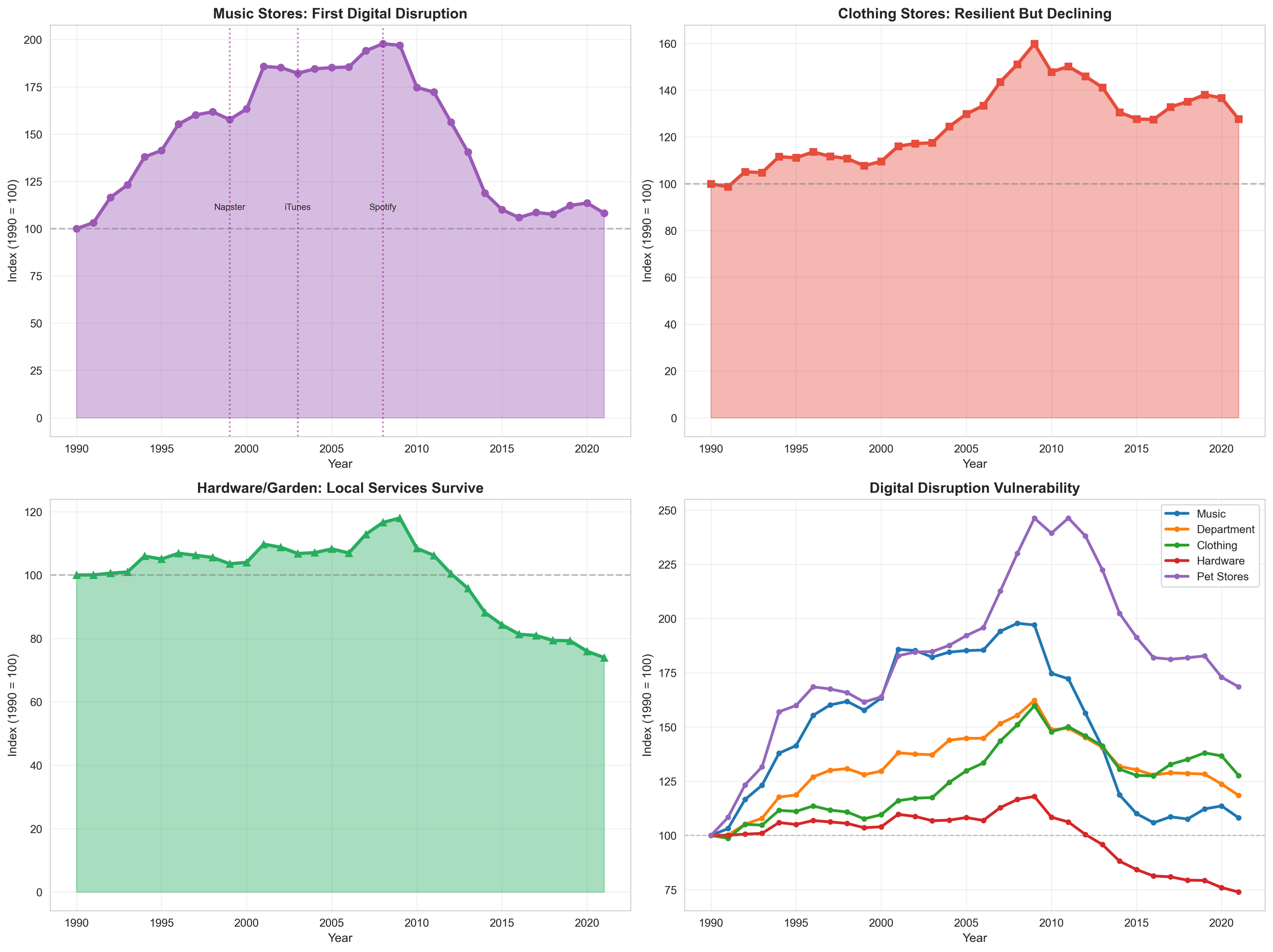

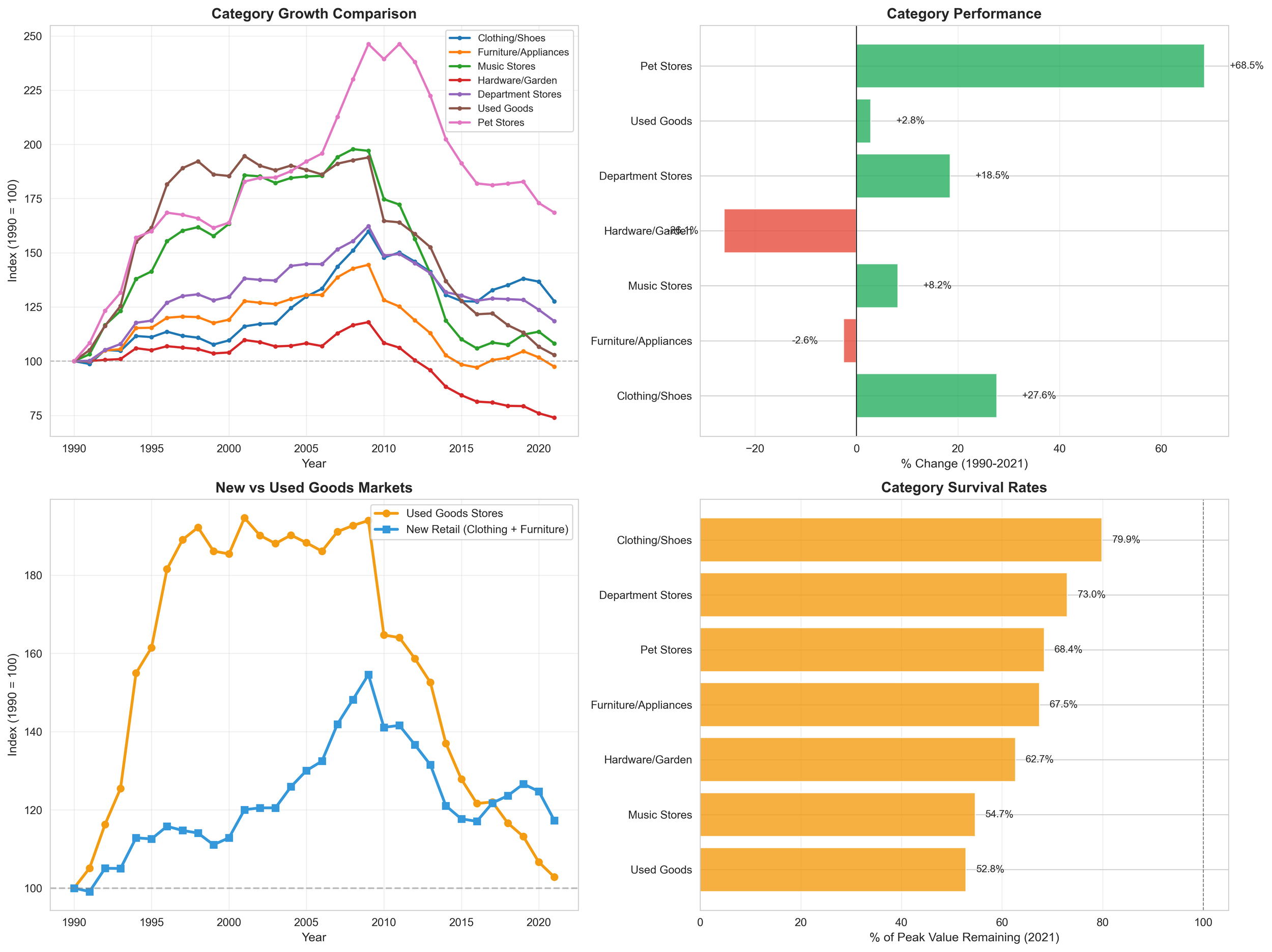

Insight 5: “advice value” saves retail from digital disruption

Digital disruption eliminates physical stores when buying is simple: the product is standardized, the risk of a wrong choice is low, and delivery is easier than visiting a store. This is why music, books, and some clothing categories moved online.

Physical retail survives when choosing correctly requires help. Stores remain valuable when customers need expert advice, products are complex or unfamiliar, mistakes are costly, or context matters (materials, sizing, safety, climate). This explains why hardware, garden, pet supplies, and home improvement remain stable.

A simple rule:

Low risk purchases → online wins

Medium risk → mixed channels

High risk → in-person wins

As products become more technical or personalized, physical retail becomes more defensible, not less. Even coffee culture reflects this, think of “Anthropic café” pop-ups.

What to watch

The dataset tracks establishments, not how people actually gather. That means many emerging third places don’t show up in the numbers at all — Discord groups that meet in person, pickleball leagues replacing tennis, church parking lots turning into farmers markets, or co-working areas inside cafés and hotel lobbies.

The next major third place may not be a venue. It may be an app, a membership, a hybrid event, or a flexible gathering model that moves between spaces.

The core point is simple: people still want places to belong. The open question is what that belonging looks like now that the old structures are gone.

Thank you for thinking with me. This piece is part of Ode by Muno, where I explore the invisible systems shaping how we sense, think, and create.

I'm curious what patterns you're noticing in your own life: where are your third places, or where did they used to be? What spaces feel like they're disappearing, and what's replacing them? Leave a comment with what resonated, or share a third place that still exists in your city. And if you want to follow this evolving conversation, subscribe to get new

The quote at the intro is from the book, Systems Intelligence. The concept of "third places" comes from sociologist Ray Oldenburg's 1989 book, The Great Good Place.

In my next post, I'll explore how urban design shapes the way we think and feel. Because some cities have bad UX and the interface you navigate daily affects more than just your commute.